The Case of the Decaying Cadaver

The sickly sweet odor of a dead body is said to be

both immediately recognizable and hard to forget. But what chemical

cocktail makes up the distinctive odor? And can GC×GC offer

investigators a forensic tool that even Sherlock Holmes would envy – the

ability to detect the ‘smell of death’?

On dit que l'odeur douce et maladive d'un cadavre est à la fois immédiatement reconnaissable et difficile à oublier. Mais quel cocktail chimique constitue cette odeur particulière ? Et le GC×GC peut-il offrir aux enquêteurs un outil médico-légal que même Sherlock Holmes envierait : la capacité de détecter "l'odeur de la mort" ?

In 2002, Arpad Vass and co-workers published the first study

monitoring the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released by decaying

bodies (1), sparking a new field of cadaveric VOC profiling (1)(2)(3)(4)(5).

Seven years later, our colleagues at the entomological laboratory at

Gembloux Agro BioTech (University of Liège) were examining the behavior

of insects as they colonized decomposing pig bodies, which involved

analyzing VOC profiles of the body headspace (6).

The complexity of the VOC mixture released by the decaying animals

meant that the entomologists soon ran into problems. Facing peak

capacity issues when using ‘regular’ one-dimensional gas chromatography

(1DGC) – even coupled with mass spectrometry - they approached us to

help them develop a superior analytical approach.

We felt the obvious answer was comprehensive two-dimensional gas

chromatography (GC×GC) time-of-flight mass spectrometry (TOFMS), as it

would allow us to separate and further identify a greater number of

components within the volatile cadaveric signature (7)(8)(9).

For us, decomposition VOC monitoring was another perfect example of how

GC×GC can make an analytical scientist’s life easier when working with

complex matrices, as it had been the case for us previously in our

metabolomics and breath analyses projects.

At that time, the trial of Casey Anthony had hit the headlines in the

United States, so the issue of decomposition VOC profiling was in the

spotlight. Anthony was accused of murdering her two-year-old daughter,

and the presence of VOCs “consistent with a decomposition event” in the

trunk of Anthony’s car was presented as evidence for the prosecution. At

the trial, forensic experts were called to testify about the

reliability of decomposition odor signatures – in this case, measured by

laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS). There was intense

disagreement between experts, highlighting the need for a more

comprehensive description of the decomposition process and its chemical

signature. We believed that exhaustive study of cadaveric decomposition

by means of GC×GC-TOFMS could help resolve this confusion, thus allowing

VOC profiles to be used as evidence in court.

You know my methods, Watson

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, A Conan Doyle (1893)

Setting out on our quest for a better understanding of the VOCs of human decay, we soon realized that most previous studies were exclusively focused on the forensic aspect of the decomposition process, while neglecting the analytical aspect – unfortunate, given that the analytical challenge is immense! The headspace of a decomposing body contains hundreds of different compounds, from most chemical families, and over a large dynamic range. Moreover, the dynamic nature of the decomposition process itself further complicates the design of VOC signature experiments. Thus, our first goal was to optimize our GC×GC-TOFMS method to perform non-targeted screening of the decaying pig headspace at various stages of decomposition.

Setting out on our quest for a better understanding of the VOCs of human decay, we soon realized that most previous studies were exclusively focused on the forensic aspect of the decomposition process, while neglecting the analytical aspect – unfortunate, given that the analytical challenge is immense! The headspace of a decomposing body contains hundreds of different compounds, from most chemical families, and over a large dynamic range. Moreover, the dynamic nature of the decomposition process itself further complicates the design of VOC signature experiments. Thus, our first goal was to optimize our GC×GC-TOFMS method to perform non-targeted screening of the decaying pig headspace at various stages of decomposition.

“For us, decomposition VOC monitoring was another perfect example how GC×GC can make an analytical scientist’s life easier when working with complex matrices.”

In doing so, we came up against the same challenges as GC×GC users in

any other field: how do we sample and introduce analytes into the

system? How do we optimize peak dispersion into the 2D space? How do we

process replicate chromatograms? How do we deal with the large amount of

corresponding data? Which statistical methods are compatible? All these

questions are still common to all studies in the field of GC×GC – and

remain hot topics at symposia like the forthcoming ISCC & GCxGC (www.isccgcxgc.com).

First, we tested three different sampling techniques: solid phase

micro-extraction (SPME), solvent extraction, and thermal desorption

(TD). TD soon emerged as the most effective method for trapping

cadaveric VOCs (10).

TD also has the advantage of preserving sample integrity during

sampling (tube loading) in body farms, storage, and shipment of tubes to

the analytical laboratory. Furthermore, with dynamic sampling and

solvent-free extraction, TD allows a representative trapping of the

decomposition headspace. In our first few studies, we carried out

chromatographic separation using a classic non-polar × semi-polar column

combination, with 5 percent phenyl siloxane as 1D and a 50 percent as

2D (8).

We later evaluated many other different phase combinations, such as

semi-polar × non-polar, and ionic liquid × non-polar. Ultimately, the

most appropriate phase combination came from our collaborators at the

Forbes lab in Australia (11),

who reported a combination of a cyanopropyle phase (Rxi-624 SilMS,

Restek) and a polyethylene glycol phase (Stabilwax, Restek) for the

efficient separation of semi polar compounds in complex VOC matrices

(for example, cadaveric decomposition and cell culture headspace).

It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, A Conan Doyle (1891)

Much of our time in those early studies was dedicated to data

handling. The first report we published in 2012 involved days of manual

data sorting in Excel spreadsheets before any statistical work could

begin – all very well for a proof-of-concept study, but not realistic

for the large number of samples needed for forensic investigations. The

implementation and use of commercially available alignment tools, such

as “Statistical Compare” in ChromaTOF (LECO Corp.) and GC Image package

(Zoex Corp.), made our lives much easier. However, simply feeding raw

data into the software won’t get the job done. One of the main problems

was separating the relevant information from artefact signals and

analytical noise. When your sample alignment generates almost 1,000

hits, you know that many of them will not be significant. Based on work

by the Synovec group (12)(13),

we decided to use a Fisher ratio (FR)-based approach to reduce the size

of our data matrix. But where should we set the cutoff to concentrate

our statistical treatments on the most significant features? We

evaluated a number of different approaches, but settled on the use of F

critical values. These values are defined by the degree of confidence we

want to apply (for example, 99 percent or 95 percent) and the two

degrees of freedom of our analysis (the number of classes and the number

of replicates in each classes) (14)(15)(16).

All compounds with a FR value above such F critical values were defined

as statistically significant. The method cuts the number of features by

10–20 percent, allowing us to focus only on the most significant

compounds for statistical treatment (14)(15)(16)(17).

“The headspace of a decomposing body contains hundreds of different compounds, from most chemical families, and over a large dynamic range.”

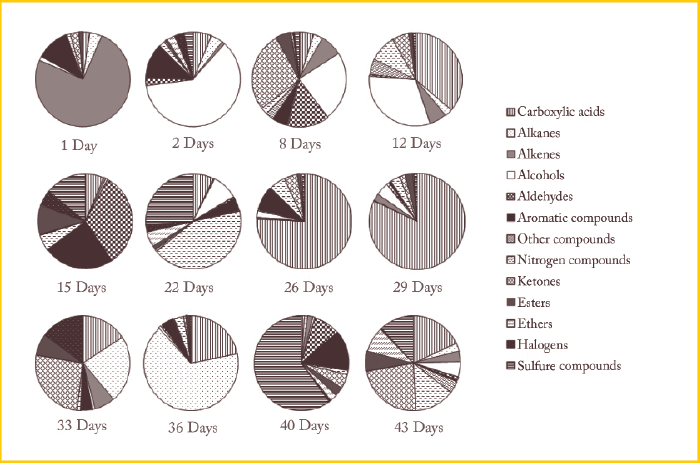

The Smell of Life

Determining an accurate fingerprint for the smell of death may prove invaluable for the recovery of bodies in disaster areas – but what of survivors buried under debris? Currently, rescuers use highly trained dogs to locate trapped survivors – a dog’s nose is a highly accurate VOC detector, and search and rescue dogs have an excellent success rate. However, dogs take a long time to train, can work only for short periods, and cannot be used in highly dangerous environments. Several groups have explored alternative routes for detecting the ‘smell of life’, using a range of technologies (C-MS, PTR-MS, SIFT-MS, MCC-IMS, FAIMS and sensor-based systems). Figure 1 shows the composition of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released by living human bodies. A group from Austria classified these compounds, and identified 11 VOCs consistently released in detectable quantities – CO2, ammonia, acetone, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, isoprene, n-propanal, n-hexanal, n-heptanal, n-octanal, n-nonanal, and acetaldehyde. This information may help scientists find new ways to sniff out disaster survivors, and so relieve the burden on canine search and rescue teams.Déterminer une empreinte digitale précise pour l'odeur de la mort peut s'avérer inestimable pour la récupération des corps dans les zones sinistrées - mais qu'en est-il des survivants enterrés sous les débris ? Actuellement, les sauveteurs utilisent des chiens très entraînés pour localiser les survivants piégés. Le nez d'un chien est un détecteur de COV très précis, et les chiens de recherche et de sauvetage ont un excellent taux de réussite. Cependant, les chiens prennent beaucoup de temps à s'entraîner, ne peuvent travailler que pendant de courtes périodes et ne peuvent pas être utilisés dans des environnements très dangereux. Plusieurs groupes ont exploré des voies alternatives pour détecter l'"odeur de la vie", en utilisant une série de technologies (C-MS, PTR-MS, SIFT-MS, MCC-IMS, FAIMS et systèmes à base de capteurs). La figure 1 montre la composition des composés organiques volatils (COV) libérés par les corps humains vivants. Un groupe autrichien a classifié ces composés et a identifié 11 COV systématiquement rejetés en quantités détectables : CO2, ammoniac, acétone, 6-méthyl-5-heptène-2-one, isoprène, n-propanal, n-hexanal, n-heptanal, n-octanal, n-nonanal et acétaldéhyde. Ces informations peuvent aider les scientifiques à trouver de nouveaux moyens de repérer les survivants de catastrophes, et ainsi alléger le fardeau des équipes canines de recherche et de sauvetage.

Reference

Reference

- P Mochalskia et al., “Potential of volatile organic compounds as markers of entrapped humans for use in urban search-and-rescue operations”, TrAC, 68, 88–106 (2015).

Multivariate statistical methods (for example, principal component

analysis, clustering, partial least squares) are increasingly used to

handle data sets issued from GC×GC analyses (18)(19).

In fact, multivariate statistics have been used and reported in almost

every GC×GC paper for the last three years. However, we question the

utility of these mathematical treatments. As we see it, one of the

important points of concern is data dimensionality. The vast majority of

mathematical models used in GC×GC are based on a classical data

dimensionality, so that there are three to five times as many replicates

(n) as the number of variables (p). Before you apply methods such as

PCA, you have to be sure of a good n/p ratio, or risk overfitting of the

data (20). The F critical approach allows us to reduce data dimensionality, with a focus on the most informative variables (12)(13). And that’s why we believe that this approach will benefit GC×GC users.

Over time, we adopted newer technologies, transposing our approach to

GC×GC coupled to high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry

(HRTOFMS). HRTOFMS offers mass accuracy below 1 ppm while maintaining

signal deconvolution capability, and can be seen as an extra dimension

for compound identification. However, this enhanced system

dimensionality makes data management even more complex and current data

processing tools suffer from significant limitations. GC×GC-HRTOFMS

profile data files are large and unwieldy, especially when considering

replicate analyses of several sample classes for statistical

comparisons. For now, our approach is to first perform all data analyses

from GC×GC-LRTOFMS, including data acquisition, data alignment, data

reduction, and statistical treatment up to isolation of features of

interest. Next, we produce GC×GC-HRTOFMS data exclusively focusing on

specific features for proper identification using two dimensional

retention time (1tR and 2tR), linear retention time (LRIs), MS

fragmentation screening in MS libraries, and accurate mass data for

molecular formulae elucidation.

“It is no longer necessary to demonstrate what GC×GC can do; instead, it is time for a full validation of the technique.”

I am the last and highest court of appeal in detection

The Sign of the Four, A Conan Doyle (1890)

GC×GC, especially coupled to TOFMS, has now become the most applied method for cadaveric decomposition profiling. It is no longer necessary to demonstrate what GC×GC can do; instead, it is time for a full validation of the technique, not just for the characterization of parameters that influence the decomposition process, but also for routine applications and evidence in court (11)(21).

GC×GC, especially coupled to TOFMS, has now become the most applied method for cadaveric decomposition profiling. It is no longer necessary to demonstrate what GC×GC can do; instead, it is time for a full validation of the technique, not just for the characterization of parameters that influence the decomposition process, but also for routine applications and evidence in court (11)(21).

There is no doubt that the additional information provided by GC×GC

will lead to major advances in our understanding of cadaveric

decomposition chemistry. GC×GC-TOFMS instruments are now being installed

in analytical laboratories of taphonomy facilities (such as body

farms), to be used for large-scale studies on the decomposition of human

remains, which will enrich current databases and provide the robustness

that has been missing in cadaveric VOC profiles presented in the

courtroom.

For the immediate future, we will focus on implementing a

quantitative approach for analysis of decomposition VOCs. To date, only

semi-quantification has been performed, and a full quantification of

biomarker candidates will lead us to a closer understanding of the

decomposition process. In addition to the headspace of dead bodies, we

are also chasing these cadaveric VOCs in a broad range of matrices,

including (suspected) grave soils, human tissues, and internal cavity

gases. Each matrix creates a new analytical challenge in terms of method

development and brings new investigative angles to the quest for

sample characterization.

There is nothing like first-hand evidence

A Study in Scarlet, A Conan Doyle (1887)

Our internal gas reservoirs project (testing the small pockets of gas inside cadavers) is a collaboration with the Center of Legal Medicine at the University of Lausanne. Laser-assisted post-mortem computed tomography is used to locate gas bubbles, and samples are taken using gas syringes (22). We then scrutinize the internal gas samples by GC×GC-HRTOFMS to complement the gas measurements performed in Lausanne with our VOC profiles. Preliminary results suggest that not all organs decompose at the same speed, a finding that may help pathologists understand causes of death and make more accurate post-mortem interval calculations (23). We corroborated these findings with further studies on organ-specific VOC production, in which various human tissues were left to decompose in a controlled environment. These tissue-based experiments have the major advantage of allowing for many more replicate experiments than when using a body farm, where one is always limited by the number of bodies available, and gets us closer to the good n/p ratio we noted earlier as being so important.

Our internal gas reservoirs project (testing the small pockets of gas inside cadavers) is a collaboration with the Center of Legal Medicine at the University of Lausanne. Laser-assisted post-mortem computed tomography is used to locate gas bubbles, and samples are taken using gas syringes (22). We then scrutinize the internal gas samples by GC×GC-HRTOFMS to complement the gas measurements performed in Lausanne with our VOC profiles. Preliminary results suggest that not all organs decompose at the same speed, a finding that may help pathologists understand causes of death and make more accurate post-mortem interval calculations (23). We corroborated these findings with further studies on organ-specific VOC production, in which various human tissues were left to decompose in a controlled environment. These tissue-based experiments have the major advantage of allowing for many more replicate experiments than when using a body farm, where one is always limited by the number of bodies available, and gets us closer to the good n/p ratio we noted earlier as being so important.

The game is afoot

The Return of Sherlock Holmes, A Conan Doyle (1903).

The profiling of VOCs released by cadavers is a continuously growing field. State-of-the-art technologies are allowing us to analyze new kinds of matrices, which opens the door to potential medico–legal applications. Moreover, a comprehensive understanding of tissue degradation chemistry will lead to improved training programs not only for cadaver dogs, but also their counterparts in search and rescue. By pinning down the differences in VOC profile between an injured person and a ‘fresh’ cadaver, we may be able to improve the efficiency of search and rescue dogs in locating survivors after a mass disaster event. It is these valuable field applications that motivate us to continue to challenge the analytical technology to its extreme.

Le profilage des COV libérés par les cadavres est un domaine en constante évolution. Les technologies de pointe nous permettent d'analyser de nouveaux types de matrices, ce qui ouvre la porte à des applications médico-légales potentielles. En outre, une compréhension approfondie de la chimie de la dégradation des tissus permettra d'améliorer les programmes de formation non seulement pour les chiens de cadavres, mais aussi pour leurs homologues en matière de recherche et de sauvetage. En déterminant les différences de profil de COV entre une personne blessée et un cadavre "frais", nous pourrions améliorer l'efficacité des chiens de recherche et de sauvetage pour localiser les survivants après une catastrophe de grande ampleur. Ce sont ces précieuses applications sur le terrain qui nous motivent à continuer de défier la technologie analytique à l'extrême.