DON’T YOU FORGET ABOUT ME

An exploration of the

‘‘Maddie Phenomenon’’ on YouTube

Julia Kennedy- en ligne le 28 octobre 2009

Journalism Studies, volume 11, 2010, issue 2

In June 2008 the search

term ‘‘Madeleine McCann’’ generated around 3700 videos on

YouTube, attracting

over seven million text responses. This research project used generic

analysis to allocate videos to categories according to their content.

Using critical discourse analysis, the nature of the comments posted

in response to the videos was then assessed. Both methods were

deployed to explore three broad research questions. First, what kind

of content were people uploading to YouTube

in response to the case? Second, where did YouTube

users position themselves in relation to the dominant discourses of

the news media in this case? Third, previous work demonstrates

evidence of ‘‘collective expressiveness, emotionality, and

identity’’ (Greer, 2004) in virtual communities structured around

cases of child murder in the United Kingdom: to what extent were

these characteristics of imagined community evident in responses to

videos? Results demonstrate that YouTube

provides a forum for a broad range of responses to the case, both

accommodating and expanding on dominant mainstream discourses.

Evidence of distinct imagined communities forming around particular

responses to the case demonstrate nuanced and complex patterns of

responses to mediated crime through YouTube,

as technology erodes the traditional boundaries between producers and

consumers of crime news.

KEYWORDS crime news;

Madeleine McCann; user-generated content; virtual community;

YouTube

En juin 2008, chercher ''Madeleine McCann'' a généré environ 3700 vidéos sur YouTube, attirant plus de sept millions de réponses textuelles. Ce projet de recherche a utilisé l'analyse générique pour répartir les vidéos dans des catégories en fonction de leur contenu. L'analyse critique du discours a ensuite permis d'évaluer la nature des commentaires postés en réponse aux vidéos. Les deux méthodes ont été déployées pour explorer trois grandes questions de recherche. Premièrement, quel type de contenu les gens ont-ils téléchargé sur YouTube en réponse à l'affaire ? Deuxièmement, comment les utilisateurs de YouTube se positionnaient-ils par rapport aux discours dominants des médias d'information dans cette affaire ? Troisièmement, des travaux antérieurs ont démontré l'existence d'une " expressivité, d'une émotivité et d'une identité collectives " (Greer, 2004) dans les communautés virtuelles structurées autour des cas de meurtre d'enfants au Royaume-Uni : dans quelle mesure ces caractéristiques de la communauté imaginée étaient-elles évidentes dans les réponses aux vidéos ? Les résultats démontrent que YouTube fournit un forum pour un large éventail de réponses à l'affaire, à la fois accommodant et s'étendant aux discours dominants du courant dominant. La preuve de la formation de communautés imaginées distinctes autour de réponses particulières à l'affaire démontre des modèles nuancés et complexes de réponses au crime médiatisé par YouTube, alors que la technologie érode les frontières traditionnelles entre les producteurs et les consommateurs d'histoires criminelles.

MOTS CLÉS nouvelles criminelles ; Madeleine McCann ; contenu généré par l'utilisateur ; communauté virtuelle ; YouTube

Introduction

In July 2008, some 15

months after her disappearance from the family holiday apartment in

Praia de Luz, British journalists reported the Portuguese police’s

decision to close the case of the disappearance of British toddler,

Madeleine McCann. This officially brought to a close one of the most

publicized manhunts of recent times. The ‘‘Maddie Phenomenon’’

referred to in the title describes the frenzy of media and public

response to the case. Leakage from the relatively contained vessels

of digitally converged corporate media was relentless; mediation of

this narrative of loss occupied spaces far outside the mainstream

margins within days. Dedicated news forums sat alongside independent

forums and blogs, missing posters of Madeleine appeared in the

virtual streets of Second Life, and a plethora of user-generated

content was uploaded to sites such as YouTube

over the weeks and months following her disappearance.

This paper explores the

role played by YouTube

in response to the disappearance of Madeleine McCann within the

broader context of the intersection between news, technology, and

community surrounding mediated crime. In what ways was it used to

extend the dialogic space around this hyper-mediated event? What kind

of content did users upload in response to the unfolding narrative in

the mainstream media? What kind

of virtual communities emerged around

the various perspectives articulated? Finally, what conclusions can

we draw about mediated crime, user-generated content and community in

late modernity?

En juillet 2008, quelque 15 mois après sa disparition de l'appartement de vacances familial à Praia de Luz, des journalistes britanniques ont annoncé la décision de la police portugaise de clore l'affaire de la disparition de la petite fille britannique Madeleine McCann. Cette décision mettait officiellement fin à l'une des chasses à l'homme les plus médiatisées de ces derniers temps. Le ''phénomène Maddie'' dont il est question dans le titre décrit la frénésie des médias et du public face à cette affaire. Les fuites des vaisseaux relativement confinés des médias d'entreprise à convergence numérique a été incessante ; la médiation de ce récit de perte a occupé des espaces bien au-delà des marges du courant dominant en quelques jours. Des forums d'information spécialisés ont côtoyé des forums et des blogs indépendants, des posters de Madeleine disparue sont apparus dans les rues virtuelles de Second Life, et une pléthore de contenu généré par les utilisateurs a été téléchargé sur des sites tels que YouTube au cours des semaines et des mois qui ont suivi sa disparition.

Cet article explore le rôle joué par YouTube en réponse à la disparition de Madeleine McCann dans le contexte plus large de l'intersection entre les nouvelles, la technologie et la communauté autour du crime médiatisé. De quelle manière YouTube a-t-il été utilisé pour étendre l'espace dialogique autour de cet événement hypermédiatisé ? Quel type de contenu les utilisateurs ont-ils téléchargé en réponse au récit des médias grand public ? Quels types de communautés virtuelles ont émergé autour des différentes perspectives articulées ? Enfin, quelles conclusions pouvons-nous tirer sur le crime médiatisé, le contenu généré par les utilisateurs et la communauté à la fin de la modernité ?

News in the YouTube

Generation

With around 100 million

video streams being viewed and some 65,000 new video clips uploaded

daily (Thomas and Buch, 2007), the observation that ‘‘YouTube

is significantly changing the way wired citizens are using and

consuming mass media messages’’ (Harp and Tremayne, 2007, p. 1)

seems evident.

The freeing up of the

ownership of news and the networking of public responses to it

afforded by Web 2.0 technologies mark one of the more significant

changes in the consumption of mass media messages in a digital era.

It is not surprising then that YouTube

has exploited its potential role in more participatory models of news

production and consumption through its dedicated ‘‘news and

politics’’ category, and in the bold statement, ‘‘We want to

see a lot more citizen journalism on YouTube’’

(YouTube Editors,

2007). In addition to the site’s potential as a conduit for

grassroots journalism is its role as a participatory space for public

responses to the unfolding narratives of mainstream news stories.

Patterns of news consumption on YouTube

reflect general shifts in consumer-led news access across the

Internet. Users come to sites with a specific news story already in

mind to seek or create further information, alternative perspectives,

and to participate in a decentralized community of information

exchange. As YouTube

news manager, Olivia Ma puts it, ‘‘news is essentially a shared

experience’’ (cited in Gannes, 2009). Drawing on Surowiecki’s

(2004) concepts of the importance of collective wisdom in shaping

societies, Santos et al. stress the importance of community in

YouTube, citing it as

an example of ‘‘the wisdom of crowds’’ (2008, p. 1).

To date, little work is

available on the nature of YouTube

responses to mainstream news stories. This work seeks to explore the

nature of communities accommodated by YouTube

in response to a particular type of news story*the child abduction

narrative.

L'actualité dans la génération YouTube

Avec environ 100 millions de flux vidéo visionnés et quelque 65 000 nouveaux clips vidéo téléchargés chaque jour (Thomas et Buch, 2007), l'observation selon laquelle " YouTube modifie de manière significative la façon dont les citoyens connectés utilisent et consomment les messages des médias de masse " (Harp et Tremayne, 2007, p. 1) semble évidente.

La libération de la propriété des informations et la mise en réseau des réactions du public à celles-ci, permises par les technologies du Web 2.0, marquent l'un des changements les plus importants dans la consommation des messages des médias de masse à l'ère numérique. Il n'est donc pas surprenant que YouTube ait exploité son rôle potentiel dans des modèles plus participatifs de production et de consommation de l'information par le biais de sa catégorie dédiée aux " nouvelles et à la politique ", et par une déclaration audacieuse : " Nous voulons voir beaucoup plus de journalisme citoyen sur YouTube " (YouTube Editors, 2007). En plus du potentiel du site en tant que conduit pour le journalisme de base, son rôle en tant qu'espace participatif pour les réponses du public au déroulement des récits des nouvelles grand public. Les modèles de consommation de nouvelles sur YouTube reflètent les changements généraux dans l'accès aux nouvelles par les consommateurs sur Internet. Les utilisateurs se rendent sur des sites avec un sujet d'actualité spécifique en tête pour rechercher ou créer des informations supplémentaires, des perspectives alternatives et pour participer à une communauté décentralisée d'échange d'informations. Comme le dit Olivia Ma, responsable des actualités sur YouTube, " les actualités sont essentiellement une expérience partagée " (cité dans Gannes, 2009). S'inspirant des concepts de Surowiecki (2004) sur l'importance de la sagesse collective pour façonner les sociétés, Santos et al. soulignent l'importance de la communauté dans YouTube, la citant comme un exemple de " la sagesse des foules " (2008, p. 1).

À ce jour, peu de travaux sont disponibles sur la nature des réponses de YouTube aux nouvelles grand public. Ce travail vise à explorer la nature des communautés accueillies par YouTube en réponse à un type particulier de nouvelles*, le récit d'enlèvement d'enfants.

Crime News and Imagined

Communities in Late Modernity

As Beck (1992) [1986])

and Giddens (1991) have noted, the unstable and fragmented social

conditions of late-modernity produce manifestations of anxiety around

identity and meaning. This is particularly notable around responses

to crime and criminality in a digital age. Negotiation of fear and

uncertainty around crime intersect with new communication

technologies to create ‘‘imagined communities structured around

collective expressive- ness, emotionality, and identity’’ (Greer,

2004, p. 115).

The mediation of the

murder, or abduction of children has always provoked powerful

communities of response, as demonstrated by the collective fear and

loathing unleashed by the Moors Murders in the pre-digital 1960s.

Increasingly, since the murder of James Bulger in 1993 to the McCann

case, localized face-to-face communication is augmented or replaced

with new forms of digital social contact and community.

The role of traditional

mediation in public perceptions of such crimes remains important.

Greer makes clear links between the sentiments expressed in

communities of online grieving in response to child murder and the

popular press’s tendency to construct narrative tropes of the

‘‘ideal victim’’ and ‘‘absolute other’’ in such

cases. Virtual

communities of grieving constructed on the foundations

of such reductive, populist binaries may appear to challenge the more

celebratory claims for the Internet as a democratic forum. The

potential of online social networks as important conduits for ‘‘the

celebration of diversity and the articulation and advancement of

alternative discourses’’ (Greer, 2004, p. 108) is, however,

significant. The popular discourses of traditional media forms may

remain, but this paper will demonstrate that they are open to

re-territorialization in a variety of ways through online

communities.

The overwhelming public

response to the McCann case on YouTube

offers an important and accessible corpus for advancing our

understanding of the ways in which databases for user-generated

content may accommodate both traditional and diverse, alternative

discourses in response to this most taboo of crimes.

Nouvelles criminelles et communautés imaginées dans la post-modernité

Comme Beck (1992) [1986]) et Giddens (1991) l'ont noté, les conditions sociales instables et fragmentées de la modernité tardive produisent des manifestations d'anxiété autour de l'identité et du sens. Ceci est particulièrement remarquable en ce qui concerne les réponses au crime et à la criminalité à l'ère numérique. La négociation de la peur et de l'incertitude liées au crime s'entrecroise avec les nouvelles technologies de communication pour créer " des communautés imaginaires structurées autour de l'expressivité collective, de l'émotivité et de l'identité " (Greer, 2004, p. 115).

La médiation du meurtre ou de l'enlèvement d'enfants a toujours provoqué de puissantes communautés de réaction, comme en témoigne la peur et la répulsion collectives déclenchées par les meurtres des Maures dans les années 1960, avant l'avènement du numérique. De plus en plus, depuis le meurtre de James Bulger en 1993 jusqu'à l'affaire McCann, la communication face à face localisée est augmentée ou remplacée par de nouvelles formes de contact social et de communauté numériques.

Le rôle de la médiation traditionnelle dans la perception publique de ces crimes reste important. Greer établit des liens clairs entre les sentiments exprimés dans les communautés de deuil en ligne en réponse aux meurtres d'enfants et la tendance de la presse populaire à construire des tropes narratifs de la "victime idéale" et de "l'autre absolu" dans de tels cas. Les communautés virtuelles de deuil construites sur la base de ces binaires réducteurs et populistes peuvent sembler remettre en question les revendications plus réjouissantes de l'Internet en tant que forum démocratique. Le potentiel des réseaux sociaux en ligne en tant que conduits importants pour " la célébration de la diversité et l'articulation et la promotion de discours alternatifs " (Greer, 2004, p. 108) est cependant significatif. Les discours populaires des formes médiatiques traditionnelles peuvent demeurer, mais cet article démontrera qu'ils sont ouverts à la re-territorialisation de diverses manières par le biais des communautés en ligne.

La réponse publique massive à l'affaire McCann sur YouTube offre un corpus important et accessible pour faire progresser notre compréhension des façons dont les bases de données de contenu généré par les utilisateurs peuvent accueillir des discours traditionnels et divers, alternatifs, en réponse à ce crime des plus tabous.

Methodology: Identifying

the Genres, and Exploring the Discourse

This study set out to

isolate the varying discourses at play in user-generated video

responses to the case, and to explore the kinds of virtual

communities clustering around them within the YouTube

population. To this end, a qualitative content analysis was conducted

to define the generic categories for the first stage of the research.

A total of 3680 videos were uploaded to the site accessible under the

generic search term ‘‘Madeleine McCann’’. The top 10 per cent

of those videos by numbers of viewers were sorted according to the

discursive position adopted in relation to the case.

Whilst mindful that a

genre is ‘‘ultimately an abstract conception rather than

something that exists empirically in the world’’ (Feuer, 1992, p.

144), in isolating ‘‘recurrent, typical features in order to

establish textual models or prototypes’’ (Larsen, 2002, p. 118),

the aim was to explore the social constructions at play in the

user-generated content and its responses.

The case has invoked a

number of dominant public discourses around child abduction,

parenting, policing, and media responses to missing children in

general. These discursive strands were clearly identifiable in the

fabric of user-generated content and its responses on YouTube,

but the texture was enriched by a number of alternative discourses,

supporting arguments for virtual spaces as a counterpoint to the

narrow range of dominant mainstream perspectives. These included

satirical or humorous responses, psychic or astrological

perspectives, forensic-based videos, and original music composed and

performed in response to the case.

In all, 13 distinctive

generic approaches to videos uploaded within the isolated sample were

identified. These were subjected to quantitative variables including

total amount of responses, amount of videos posted and total number

of views. Table 1 offers a brief description of the generic

categories emerging, and relevant numerical data, and is sorted

according to the number of total responses elicited by each

category.

As Table 1 reveals,

videos assuming the form of tributes to Madeleine McCann, and those

directly expressing hostility to the McCann family produced the most

traffic in terms of responses elicited. This was particularly

interesting in the case of the hostility videos, which represented

only 5 per cent of the overall number of videos posted, yet drew 20

per cent of total text responses, and 24 per cent of total video

responses. Since the study was concerned with virtual community

formation around the generic discourses, these formed the data for

the next stage of the research.

Méthodologie : Identifier les genres et explorer le discours

Cette étude a pour but d'isoler les différents discours en jeu dans les réponses vidéo générées par les utilisateurs sur l'affaire, et d'explorer les types de communautés virtuelles qui se regroupent autour d'eux au sein de la population YouTube. À cette fin, une analyse de contenu qualitative a été menée pour définir les catégories génériques de la première étape de la recherche. Un total de 3680 vidéos ont été téléchargées sur le site accessible sous le terme de recherche générique ''Madeleine McCann''. Les 10 % de ces vidéos les plus consultées ont été triées en fonction de la position discursive adoptée par rapport à l'affaire.

Tout en gardant à l'esprit qu'un genre est "en fin de compte une conception abstraite plutôt que quelque chose qui existe empiriquement dans le monde" (Feuer, 1992, p. 144), en isolant "des caractéristiques récurrentes et typiques afin d'établir des modèles ou des prototypes textuels" (Larsen, 2002, p. 118), l'objectif était d'explorer les constructions sociales en jeu dans le contenu généré par les utilisateurs et leurs réponses.

L'affaire a invoqué un certain nombre de discours publics dominants sur l'enlèvement d'enfants, la parentalité, le maintien de l'ordre et les réponses des médias aux enfants disparus en général. Ces courants discursifs étaient clairement identifiables dans le tissu du contenu généré par les utilisateurs et ses réponses sur YouTube, mais la texture a été enrichie par un certain nombre de discours alternatifs, soutenant des arguments en faveur des espaces virtuels comme contrepoint à la gamme étroite de perspectives dominantes du courant dominant. Il s'agissait notamment de réponses satiriques ou humoristiques, de perspectives psychiques ou astrologiques, de vidéos à caractère médico-légal et de musique originale composée et interprétée en réponse à l'affaire.

Au total, 13 approches génériques distinctes des vidéos téléchargées dans l'échantillon isolé ont été identifiées. Ces approches ont été soumises à des variables quantitatives, notamment le nombre total de réponses, le nombre de vidéos mises en ligne et le nombre total de vues. Le tableau 1 offre une brève description des catégories génériques émergentes, ainsi que des données numériques pertinentes, et est classé en fonction du nombre total de réponses suscitées par chaque catégorie.

Comme le révèle le tableau 1, les vidéos prenant la forme d'hommages à Madeleine McCann et celles exprimant directement de l'hostilité envers la famille McCann ont généré le plus de trafic en termes de réponses suscitées. Ceci est particulièrement intéressant dans le cas des vidéos d'hostilité, qui ne représentent que 5 % du nombre total de vidéos postées, mais qui ont suscité 20 % du total des réponses textuelles et 24 % du total des réponses vidéo. Puisque l'étude portait sur la formation d'une communauté virtuelle autour des discours génériques, ceux-ci ont constitué les données de l'étape suivante de la recherche.

Concerned to analyse the

ways in which language is used in social contexts, discourse analysis

has been defined as an exploration of ‘‘who uses language, how

why and when’’ (Van Dijk, 1997, p. 2). The first 100 text

comments posted in response to the top 10 videos (by view count) in

both the ‘‘Tribute’’ and ‘‘Hostility’’ categories

were analysed using emergent coding. Taking into account the

inevitable limitations imposed by purely textual analysis, the aim

was to identify dominant discursive themes, and the nature of the

interactions between posters.

Soucieuse d'analyser la manière dont le langage est utilisé dans des contextes sociaux, l'analyse du discours a été définie comme une exploration de " qui utilise le langage, comment, pourquoi et quand " (Van Dijk, 1997, p. 2). Les 100 premiers commentaires textuels postés en réponse aux 10 premières vidéos (par nombre de vues) dans les catégories " Hommage " et " Hostilité " ont été analysés à l'aide du codage émergent. En tenant compte des limites inévitables imposées par une analyse purement textuelle, l'objectif était d'identifier les thèmes discursifs dominants et la nature des interactions entre les posters.

The Tribute Video

Tribute videos

constituted 56 per cent of the total videos posted under the generic

search term, attracted more than four and a half million views, and

stimulated 56 per cent of texts posted across the overall sample.

These videos were generally produced on standard home-editing

software, displaying a montage of images of Madeleine taken from

mainstream media sources, and employing background music from

poignant popular songs. Text embedded into the videos described

Madeleine’s disappearance, and implored viewers to help find her.

Family and holiday snaps and video footage are standard visual

conventions in the mainstream abduction story. Their ubiquitous

presence in this generic category demonstrates a high degree of

intertextuality with popular news and documentary forms.

The popularity of this

genre supports Greer’s (2004) observations of a sense of community

based on vicarious participation in the suffering of those affected

by child

murder. The lack of a clearly identifiable absolute other,

combined with the unsolved mystery of the child’s whereabouts

seemed to shift the focus of community consensus in this genre away

from vigilantism towards a collective focus on finding Madeleine.

Many of the videos and responses contain direct addresses to a

notional abductor, and to Madeleine herself:

Don’t worry Maddy okay? We are doing everything we can. I am praying for you to return safely. And to you people. Please bring Maddy back. We have money if that is your case, please just bring her back . . . Thank you. (Response to YouTube, 2007b)

Others appealed directly

to the YouTube

community to ‘‘fight’’ such crimes together:

Lets get this baby back ... if everyone of us gave a buck in our own currency ... we would all have done something not only to get Madeleine back but we would be sending out a clear message to the people who have her*That we will no longer allow these crimes to go on*Please you tubers lets fight them to-gether. Lets do something we can all be proud of!!!!

Such postings and their

responses indicate a consensual notion of universality around

YouTube’s potential

reach, and hint at a strong sense of imagined community at work

amongst the respondents. This strong consensus emerged around a

number of discursive themes framing responses to the case, easing the

facilitation of emergent coding for the discourse analysis element of

the research in this genre.

Les vidéos d'hommage constituaient 56 % du total des vidéos publiées sous le terme de recherche générique, ont attiré plus de quatre millions et demi de vues et ont stimulé 56 % des textes publiés dans l'ensemble de l'échantillon. Ces vidéos ont généralement été produites à l'aide d'un logiciel de montage domestique standard, affichant un montage d'images de Madeleine provenant de sources médiatiques grand public et utilisant une musique de fond provenant de chansons populaires poignantes. Le texte intégré dans les vidéos décrivait la disparition de Madeleine et implorait les spectateurs d'aider à la retrouver. Les photos de famille et de vacances ainsi que les séquences vidéo sont des conventions visuelles standard dans les histoires d'enlèvement grand public. Leur omniprésence dans cette catégorie générique démontre un haut degré d'intertextualité avec les nouvelles populaires et les formes documentaires.

La popularité de ce genre soutient les observations de Greer (2004) concernant le sentiment de communauté basé sur la participation par procuration à la souffrance des personnes affectées par le meurtre d'un enfant. L'absence d'un autre absolu clairement identifiable, combinée au mystère non résolu de l'endroit où se trouvait l'enfant, semble avoir déplacé le consensus de la communauté dans ce genre, du vigilantisme vers un objectif collectif de retrouver Madeleine. De nombreuses vidéos et réponses contiennent des adresses directes à un ravisseur fictif et à Madeleine elle-même :

Ne t'inquiète pas Maddy, d'accord ? Nous faisons tout ce que nous pouvons. Je prie pour que tu reviennes saine et sauve. Et à vous tous. S'il vous plaît, ramenez Maddy. Nous avons de l'argent, si c'est le cas, ramenez-la simplement... Merci. (Réponse à YouTube, 2007b)

D'autres ont lancé un appel direct à la communauté YouTube pour qu'elle " lutte " ensemble contre ces crimes :

Ramenons ce bébé... si chacun d'entre nous donnait un dollar dans sa propre monnaie... nous aurions tous fait quelque chose, non seulement pour ramener Madeleine, mais aussi pour envoyer un message clair aux personnes qui la détiennent... que nous ne permettrons plus que ces crimes se poursuivent... S'il vous plaît, chers internautes, combattons-les ensemble. Faisons quelque chose dont nous pouvons tous être fiers. ! !!!

Ces messages et leurs réponses indiquent une notion consensuelle d'universalité autour de la portée potentielle de YouTube, et laissent entrevoir un fort sentiment de communauté imaginaire à l'œuvre parmi les répondants. Ce consensus fort a émergé autour d'un certain nombre de thèmes discursifs encadrant les réponses au cas, facilitant la facilitation du codage émergent pour l'élément d'analyse du discours de la recherche dans ce genre.

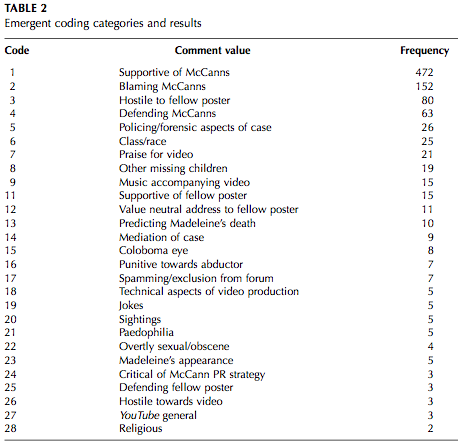

Table 2 sets out the

broader values and themes identified during the emergent coding

phase.

It is clear that the

predominant theme in the responses recorded was that of support for

the McCann family. Combined with those defending the McCanns and

expressing support for the video, the 550 overwhelmingly positive

comments constitute 55 per cent of the responses to videos in this

genre. The 32 (3.2 per cent) comments demanding punishment for the

supposed abductor, referring to paedophiles, alleged sightings of

Madeleine, and Madeleine’s appearance were also overwhelmingly

positive towards the McCanns.

However, there was also

some strong contestation, with 158 (15.8 per cent) comments either

directly or indirectly hostile towards the McCanns. These included

some direct attacks on the ethos of collective positive thinking

underpinning the more community-oriented postings. Implications of

naivety, ineffectiveness and failure to address the McCanns’ own

perceived responsibility for their plight were common themes:

We do not live in a Care Bear world; it is brutal, and statistically speaking the chances of her coming home are extremely slim. Staying positive is not going to bring her home. It is unfortunate that she was abducted. However, the parents have only themselves to blame. One never leaves a child alone to go out for the evening. For God’s sake, these were toddlers! (Response to YouTube, 2007a)

The 26 (2.6 per cent)

comments about the policing and forensic aspects of the case ranged

from criticism of the Portuguese police in accusing the McCanns to

criticism for not finding them guilty. The 19 (1.9 per cent) comments

about missing children in general displayed some consensus around a

perceived unfair focus by the mainstream media on the disappearance

of just one child:

Yes it is bad their girl has gone missing. What is worse is the fact that they are craving all the attention they can get, when there are thousands of other missing children in the UK . . . The media is too bloody sensationalist and is playing with your minds. (Response to YouTube, 2007a)

This debate around the

perceived privileged status afforded to this case by the media

developed along a number of lines, but most predominately those of

class and race:

When you search Madeline McCann (1 person) you get 1,490 results. When you search Starving African Kids (millions of people) you get 71 results. (Response to YouTube, 2007a)

The remaining 215 (21.5

per cent) of comments comprised a number of discourses ranging from

the technical aspects of video production, music used, alleged

sightings, jokes and comments of a sexual nature and debate around

YouTube itself.

The notable repetition of

a number of key words generated a second-stage discourse analysis of

this sample seeking to isolate common mythical or linguistic tropes.

Table 3 shows some of the words recurring with more or less frequency

throughout the postings.

The word ‘‘parents’’

occurred most frequently, registering on 239 occasions across the

1000 comments analysed (made up from the first 100 postings in

response to the top 10 videos by view). Alongside notable recurrence

of the words ‘‘left/leave’’, ‘‘alone/own’’, ‘‘blame’’

and ‘‘fault’’, the word ‘‘parents’’ was central to

the ongoing debate around

responsible parenting

sparked by the children being left alone. Grant notes how

identification as a parent seemed to provide a consensual basis from

which to demand severe punishment for the killers of three-year-old

James Bulger (2007, p. 106). Whilst parental status marked the

position from which many posters made their points, identification

with Kate and Gerry McCann was markedly less consensual in this

sample. Postings tended to divide into either vitriolic criticism,

empathetic defence, or a confused mix of both. Many contributors

argued defensively that losing Madeleine was punishment enough for

the McCanns’ fateful decision to leave the children alone, but the

following comment broadly represents the emotionally affective tone

and sense of individual virtue characterizing responses in this

genre:

what her parents are feelin at the moment Ii don’t wish that on anyone, but if i had a kid i would never, ever leave them alone in a room. and the parents were nurses or something weren’t they? they should have known better. (Response to YouTube, 2007b)

Note how the poster opens

with an attempt at empathy, proceeding to putative claims for their

own projected behaviour had they been parents themselves, and

ultimately reverting to finger-wagging blame. This supports Mick

Hume’s observations of the schizophrenic, ‘‘emotional

exhibitionism’’ characterizing public responses to the mediation

of Kate and Gerry McCann as dual symbols of both abject victimhood

and suspect parenthood (Hume, 2007). It also represents the highly

individualized, emotionally affective responses that characterized

this case in general, leading Tim Black to his somewhat bleak

prophecy of ‘‘the degradation of the public sphere’’ (Black,

2008).

In terms of the supposed

abductor, the relative popularity of the words ‘‘sick’’ and

‘‘sicko’’ articulate a collective sense of a diseased or

perverted individual at large. Despite the fact that ‘‘sexual

violence against children is most often perpetrated by someone they

know’’ (Kitzinger, 2004, p. 128), the enduring popularity of the

stranger-danger myth is shored up by formulaic narratives in the

popular press. Intimations of universal threat to readers, an ongoing

narrative from abduction to conclusion (very often the tragic

discovery of a body), and available imagery from the family album or

CCTV footage make these stories hugely attractive to popular

journalistic markets. The paedophile becomes a consensual symbol of

‘‘absolute other’’, a deviant identity that can be pitted

against constructions of virtuous identity to establish ‘‘a sense

of membership and belonging’’ (Greer, 2004, p. 114). These binary

structures characterize allegiances in response to previous sexual

murders of young, photogenic children (Sarah Payne in 2001, Milly

Dowler in 2002, Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman in 2003), and become

stock repertoires for negotiating anxiety around crime:

These emotional and expressive adaptations*empathising with the victim, demonising and denouncing the other, both articulated and reinforced in mediatised discourses* comprise key constituents of the repertoire people use to negotiate the problem of crime. (Greer, 2004, p. 113)

The idealised

construction of Madeleine manifest in the recurrent use of the words

‘‘angel’’, ‘‘innocent’’, ‘‘beautiful’’, and

‘‘cute’’ exemplifies personal identification through symbolic

signifiers of perfect childhood:

I miss you, you little angel! (Response to YouTube, 2007b)

Such a beautiful little girl... the person who abducted her needs to burn in hell! . . . Please Let Maddy go, give her back to her mummy n daddy. (Response to YouTube, 2007a)

Constant references to

her as ‘‘Maddie’’ or ‘‘Maddy’’, despite the family’s

dislike for the shortened form of her name, indicate an imaginary

collective intimacy with the child. The ‘‘Maddie’’ to whom

these videos pay tribute is as divorced from the exigencies of real

life as the ‘‘sickos’’ and ‘‘paedos’’ constructed as

her putative abductor, and mirrors strongly the sentiments of the

popular press. These are effectively expressed in The Sun’s

headline, ‘‘‘Maddie’ perv quiz’’ for a story published on

10 June 2009 about the police questioning of convicted paedophile

Raymond Hewlett in connection with Madeleine’s disappearance.

As with the discourses of

parenting, the high degree of consensus and mutual support generally

was again disrupted by threads suggesting that the McCann family were

profiting financially from the loss of their daughter:

I already know for a fact that the parents pulled in some insane amount of euros for their plight. They should thank god that their child is a cute little blonde girl because if she had some sort of disfigurement then they would get jack shit from this story. (Response to YouTube, 2007a)

This expresses a common

sentiment that the McCanns were being aided by the media, for whom

Madeleine represented the perfect victim for a lucrative narrative of

tragic loss. Similarly, comments also addressed suspicion for what

was regarded as a manipulative PR machine set up by the family, and

supported by much of the mainstream media.

A significant web of

threads emerged based on deliberately provocative claims by the

poster that they were personally responsible for the abduction, and a

number of postings alluded graphically to the imagined sexual nature

of Madeleine’s supposed demise. These comments often attempted to

deliberately disrupt the strong sense of consensus and hope created

by the more positively framed comments. It is notable, however, that

all dissenting comments were treated with hostility by other posters

to the tribute videos, many of them attracting aggressive responses,

and being marked as ‘‘spam’’ by other forum users.

From a diachronic

perspective, the number of tribute videos uploaded peaked around

initial mediation of the abduction itself, and continued steadily up

until September (20 per cent of videos posted in May 2007, and 80 per

cent posted before Kate McCann being declared arguida1 on 7 September

2007). During this period, activity increased around celebrity

interventions such as those by David Beckham, and J. K. Rowling, and

to alleged sightings of Madeleine reported in the media.

The Hostility Video

These videos articulated

a direct antipathy to the McCann family and their conduct throughout

the case, and took a variety of structural forms. Some included

edited clips from existing mass media with the producer’s own

perspective embedded into the video via voice-over or text. Others

consisted of the producer voicing their opinions direct to camera.

Dominant amongst sentiments in this genre were accusations of lying,

manipulation and negligence levelled against the McCann family and

their entourage.

The 28 hostility videos

represented just 7.5 per cent of the entire sample, and attracted

just 5 per cent of total views. However, they drew nearly 20 per cent

of text responses, and over 24 per cent of video responses in total.

Some 82 per cent of the hostility videos were posted in response to

other videos, and around 43 per cent attracted video responses from

fellow YouTube users,

giving this genre the most marked incidence of video to video

dialogue. Taking into account the high levels of text response, it

produced the most dialogic community in general. That this occurred

despite the relatively low proportion of videos, and significantly

minimal views attracted across the sample as a whole, made the

patterns of response in this specific genre all the more notable.

In contrast to the

tribute genre, the collective construction of idealized victim and

absolute other through a lexicon of binaries, and the articulation of

imagined group activity were not immediately discernible here. The

character of the exchanges was very different, with many comments

(26.2 per cent) directly expressing hostility or support towards the

video or the poster personally. Personal interaction between

respondents was strongly evident, resulting in a less consensual,

more dialogic form of exchange.

Producers themselves

tended to be much more active in the forum debate surrounding their

videos. These social patterns of ‘me-centred’ networks could

potentially be read as supporting Manuel Castells’ (2001) vision of

contemporary Internet commu- nication as a form of networked

individualism. These are distinct from the cohesive communality of

Howard Rheingold’s (1993) virtual communities, more evident in

the

‘‘tribute’’ genre, although both ultimately extrapolate

to democratic revival through the public agora of cyberspace.

Alternative readings, however, might relate ‘‘the complex series

of proximities between free speech discourses, infotainment media and

penal escalation’’ (Grant, 2007, p. 94) in online communications

about murder more closely to ‘‘technological populism’’ than

to representative democracy or individualism.

This study was

particularly interested to test these perspectives in the hostility

genre which, initially, seemed to provide a dialogic space for

resisting mainstream mediations around the case in line with some of

the more celebratory claims for the Internet as an alternative public

sphere.

Many of these videos

provide a counter-voice to what is seen to be an unquestioning

support for the McCanns from certain sections of the media, and

establishment in general:

Yeah pick up the phone and ask British Government to stop interfering into this criminal matter, phone Mr Mitchell and ask him just to shut up as everyone is tired listening to him, please phone British Social Services demanding them to condemn McCanns conduct as an example of negligent parenting, phone Sky News and British newspapers demanding a fair coverage of the story and finally give a call to McCanns and tell them to confess! (Response to YouTube, 2007f)

Tropes of class

inequality, negligent parenting, uncritical mediation of the case,

poor policing, and deliberate ‘‘spin’’ from the McCann family

were strongly evident in the videos and their responses. This

certainly indicates potentially democratic resistance to the dominant

discourses unfolding in the mainstream media as the case progressed.

From a temporal perspective, postings to the hostility genre tended

to align with new strands of forensic evidence and developments in

the policing of the case as it progressed in the media. Twenty-four

of the 28 videos in this category were posted after 7 September 2007,

the point at which Kate McCann was declared arguida by the Portuguese

police. The period between 7 and 10 September provoked a particular

frenzy of reporting in the British media, with reports of Kate

McCann’s refusal to answer police questions, Gerry McCann being

formally declared arguido on the 8 September, and the couple’s

high- profile return to their home in Leicestershire on the 9

September. On 10 September, the media reported that the Portuguese

police had DNA proof that Madeleine’s body had been in the boot of

the family’s hired Renault. These developments appear to have

incited much of the activity in this genre, and formed the basis of

many of the discussion threads:

Brainwashing has not worked. Read the comments on the online press and you will see the majority of people are against them not answering police questions. (Response to YouTube, 2008b)

These are Kate & Gerry’s explanations for DNA & the smell of a dead body (picked up by sniffer dogs) being present in the boot of their hire car after Maddie went missing. The DNA was the children’s dirty nappies in the boot. The ‘smell of death’ was rotting meat that Gerry was taking to the dump. Visit to the pope? 3 hail Mary’s will not wash the blood from your hands Kate and Gerry!!’’ (Response to YouTube, 2008a)

The more dynamic

relationship with the unfolding narrative exhibited by these videos

also underpinned a clearer sense of democratic debate in the

communities of response. It should be noted, however, that many of

these videos and responses demonstrated harshly punitive attitudes to

the McCann family, and an air of ‘‘conspiracy

theory’’. Many

of the videos mimicked the style of docudrama, employing sinister

music, lighting, and aesthetics of the contemporary forensic drama to

reinforce their points. In this sense then, Grant’s observations of

technological populism and the influence of ‘‘infotainment

media’’ was also evident in this category.

Throughout contributions

in this category, blatant hostility towards Kate and Gerry McCann and

their perceived supporters was often framed as a plea for ‘‘justice

for Madeleine’’. As in the tribute section then, Madeleine is

idealised as a victim, but in very different ways. At times, Kate and

Gerry McCann themselves are constructed as ‘‘absolute other’’,

naively supported by a compliant media and establishment.

Four of the top 10 videos

(by view) in the ‘‘hostility’’ genre were direct-to-camera

addresses by the poster. Three of those were by the same person, an

ex-user of the Mirror forums on the McCann case who achieved some

notoriety in the global media as the ‘‘woman from Rothley’’.

She argued vehemently that lenient treatment of the McCanns was a

class issue, and that social services would have been quick to punish

a working- class family under similar circumstances. The three videos

by this poster, all entitled ‘‘My Madeleine McCann opinion’’,

tended to divide the respondents into those directly supporting or

attacking her personally for her opinions, rather than simply

dividing by opinion:

This lady is saying what thousands of decent British parents think*well done!!!!! (Response to YouTube, 2007e)

Supportive comments like

this indicate a sense of imagined community constructed around

consensus on ‘‘decent’’ parenting, for which the poster is

celebrated as a courageous spokesperson. Others chose to align with

the poster in more clearly articulated terms of class allegiance:

Good on you for speaking your mind, but it’s always been the same way: money and position buy freedom and unaccountability. Even if not guilty of murder, you’d think by now the McCann’s would have been interviewed by a social worker or made to do a ‘‘parenting course’’ due to their neglect. Ha ha! Fat chance. That’s only for people who DON’T have money and position*PARTICULARLY pertinent in a class-based society like England’s. (Response to YouTube, 2007e)

Not all of the

respondents supported the woman from Rothley’s views. Some actively

challenged her right to use this medium to comment on the case at

all:

How egotistical and sad must you be to think anyone would actually give a shit about your opinion on a case that has already had too much attention given to it in the first place? Unless you have evidence or something, I don’t see why you’d think the world is owed a crappy webcam recorded video of yourself giving your inner thoughts? What makes you special . . .? (Response to YouTube, 2007e)

‘‘What makes you so

special?’’ challenges the poster’s right to articulate her

personal perspective in the absence of ‘‘evidence’’. Her

argument is vilified as irrational and over-reliant on the personal

and emotional dimensions of response, similar to critiques of public

response referred to in the previous section (Black, 2008; Hume,

2007). Despite such negative responses, its position as an important

counter-voice to what were perceived as the reductive narratives of

mainstream journalism remained strong amongst the discussion

threads:

You’ve got bigger balls than most of the male ‘‘journalists’’ in the UK media who have played their sorry part in whitewashing this whole case. Well said hen! (Response to YouTube, 2007e)

In fact, opinions about

the uncritical media attention attracted by this case were endemic

across the genre:

the tragic incident shows the stupidity and mindlessness of british media. the quality of democracy depends on the quality of media . . . (Response to YouTube, 2007c)

I . . . wondered if the Brit press would’ve been quite so sympathetic*and sycophantic* towards the McScams if Maddie had been found floating face down in the pool after being abandoned by her so-called parents. (Response to YouTube, 2007d)

No they haven’t been punished at all. The British press fawn all over them as though they were The Virgin Mary and Joseph back to life! (Response to YouTube, 2007d)

This common sentiment

also finds its way into threads actively celebrating YouTube

as an important alternative site for critical expression:

Well done, son. A fellow critical thinker. There’s far too many sheeple on this earth that believe everything the meedja tell them. If I have one negative thing to say about your rant it would be: get more educated, tone down on the swearing and practise being more funny. But, I applaud your freedom of expression. (Response to YouTube, 2007c)

Whilst largely

celebratory of the producer’s willingness to contest mainstream

consensus, this comment again articulates a sense that freedom of

expression in user- generated content ought to be more than just a

‘‘rant’’ to be effective. This poster’s suggestions for

parameters in terms of discursive quality and presentation again draw

on a perceived need for rationality (‘‘get more educated, tone

down the swearing’’) alongside the ability to entertain through

this format (‘‘practise being more funny’’).

The much stronger sense

of ongoing dynamism in relation to external events that characterized

this genre was also demonstrated by comment drawing on other cases

involving child abduction occurring over the period of mediation of

the McCann case. The disappearance of nine-year-old Shannon Matthews,

from her home in Dewsbury, Yorkshire some nine months after

Madeleine’s disappearance, and the different media treatment of

this case generated some interesting threads. Subse- quently,

Shannon’s mother and her partner were found to have orchestrated

the child’s ‘‘abduction’’ themselves, but when the case

broke many YouTube

posters expressed a strong sense of unequal treatment from the media

and establishment in general to the case:

I do not think Mrs. Matthews is going to see the Pope anytime soon either. Gosh, just think of the blanket high profile coverage given to the vicious pair. Top reporters flown all the way out the Portugal from all the channels; interview after interview, the Prime Minister, Becks, Richard Branson, Philip Green, private jets . . . The media, in the words of Gore Vidal, is ‘‘corrupt, stupid and vicious.’’ Crawling to? the rich and powerful is what they do best. (Response to YouTube, 2008a)

Attitudes to Fiona

MacKeowan, mother of teenager Scarlett Keeling murdered whilst

holidaying with her family in Goa in February 2008, were also seen by

posters as harsh in comparison to the perceived support given to Kate

McCann.

This category was also

distinct in terms of a strong sense of community formed in response

to what was seen as unfair exclusion from ‘‘pro McCann’’

public debates and forums. This was underpinned by the perception

that organized McCann supporters were infiltrating YouTube

to block or contest anti-McCann sentiments through disruptive

posting, or ‘‘trolling’’.

in the YouTube The number of McTrolls has increased tenfold in the past week*dozens of new names joining YT just to comment on videos about the McCanns. They must be desperate for not being able to control internauts to the same extent they control other media. (Response to YouTube, 2008b)

This poster clearly

perceives YouTube as

a space that the ‘‘desperate’’ McCann support team would find

more difficult to control than other media forms.

This genre also responded

to activity in the wider blogosphere in general. The closing of the

Mirror forums after alleged pressure from McCann PR representative

Clarence Mitchell unleashed a rash of angry responses across the

Internet. The anti-McCann site, ‘‘The 3 Arguidos’’,2 taking

its title from the naming of Kate and Gerry McCann and expat resident

of Praia de Luz, Robert Murat, as official suspects or Arguidos by

the Portuguese police, was set up as an alternative site for

dissenting voices. Many of the contributors in the hostility category

maintained links to The 3 Arguidos site, and the one video in the

‘‘competition’’ category was a montage of entries for a logo

for The 3 Arguidos website. A sense of the McCann ‘‘PR machine’’

setting out to control dissenting voices on the Internet remained a

strong theme throughout the genre.

Responding to the McCann

Case Through YouTube:

Democracy in Action, or Technological Populism?

Thirteen distinct generic

approaches were identified in the top 10 per cent (by view) of 3680

videos uploaded to YouTube

in response to the case. Alongside around seven million responses

attracted by the 368 videos sampled, there was certainly strong

evidence of a broad reach of discursive positions within the

database. To some extent the potential for increased participation

and plurality in the consumption of news narratives aligns with the

optimistic predictions of Rheingold (1994) and Castells (2001). This

paper has, however, demonstrated the need for caution in

extrapolating this to a picture of democratic rational debate around

child abduction.

Issues of crime and

criminality are particular hostages to the fortunes of mythical

structures in news narratives. Contextualizing the findings here

within Greer’s notions of virtual grieving in imagined communities

allowed the study to explore whether user- generated video might

extend discourses beyond the reductive binaries so often employed in

popular news frames.

The communities emerging

around the tribute videos accommodated some dissent in the ranks of

respondents, largely concerned with issues of over-mediation of the

case in relation to other missing children, and class-based

privileging by the media. However, on the whole, these videos and

their responses fit quite closely with Greer’s imagined communities

formed around consensual anxiety concerning notions of risk in

late-modern society. This was repeatedly demonstrated through

representation of Madeleine as

idealized victim, and a kind of

generic ‘‘risk’’ or ‘‘danger’’ standing in for an

unidentified absolute other. This sense of external, diffuse danger

invoked by the lack of a known perpetrator was consistently pitched

against discourses constructing the family unit as a locus of love

and safety in a dangerous world. The fact that Madeleine was actually

on holiday with her family when she was abducted does not appear to

disrupt the symbolic power of family as sanctuary that characterizes

many of the posts, such is the power of its symbolism. This

underpinned both those supportive posts imploring the abductor to

return Madeleine to the loving safety of her family, and the more

critical perspectives vilifying the McCanns for their failure to

uphold the symbolic sanctuary of the family unit.

The aesthetic of the

videos in this category was highly redolent of the type of tribute

videos placed on dedicated online memorial sites. There was certainly

evidence here of grieving as ‘‘public performance’’ (Malik,

2008), a vicarious sharing of a distant family’s pain, both

consensual and highly emotive in its virtual expression. As in Frank

Furedi’s notions of ‘‘mourning sickness’’ articulated in

the wake of Princess Diana’s death, social problems are

re-articulated in emotional terms in a society where the boundaries

between private and public increasingly overlap.

In the 1995 novel

Fullalove, the late Gordon Burn’s fictional cynical tabloid hack,

Norman Miller, refers to the bouquets of the impromptu pavement

memorials that mark the site of the latest child abduction or brutal

sex-crime as ‘‘just another variety of urban utterance’’

(Burn, 1995, p. 4). That the urban shrine has moved online and become

global in the case of the disappearance of Madeleine McCann

demonstrates the ability of technology to impact on traditional

social rituals. A sense of ritual response around the YouTube

tributes was imbued by a clear tendency to construct grieving for an

unknown child around reductive binaries drawn from the narratives of

popular mainstream news media. To some extent then, it is possible to

read YouTube’s

parade of tribute videos to Madeleine as digital bouquets of

affective self-expression piling up in virtual spaces rather than the

urban pavements of the material world.

Although some dissenting

voices in the tribute genre attempted to disrupt the consensual

grieving and support, there was little evidence of reasoned debate

around the social issues raised by the case. In this category at

least then, Rheingold’s (1994) utopian notion of virtual

communities, or Castells’ (2001) vision of networked individuals

working across cyberspace towards democratic expression were to a

large extent superseded by the more populist, emotive type of

imaginary community referred to by Greer (2004) and Grant (2007).

The ‘‘hostility’’

genre, however, produced smaller but much more vociferous dialogic

groups clustering around user-generated content varying from direct

to camera criticisms of the McCann family, to some fairly

sophisticated ‘‘docu-drama’’-style videos. The aesthetic in

the latter clearly drew on popular cultural forms of crime

programming and fiction.

The marked linguistic

consensus of the tribute genre was not present here. This genre was

characterized by strident questioning of mass media and establishment

compliance. Unlike the tribute genre, where the anonymity of the

abductor diffused a desire for penal escalation into a more

generalized sense of threat and fear, the hostility genre was marked

by harsh punitive sentiment towards the McCanns, and dissatisfaction

with the criminal justice system. The tendency here for debate to

relate outside of the communities of response to external events

contributed to a dynamic dialogue extending across time and space.

Contributions to the tribute genre appeared more synchronically

fixed

around the abduction itself and its immediate aftermath. Although the

democratic implications of having a forum to speak out against state

and media ineffectiveness, and Castell’s vision of networked

individuals debating public policy and action across the cyber divide

can certainly be used to contextualize some of the discursive

phenomena on these forums, the aesthetic of many of the videos and

the harsh punitive calls and exclusivity shown to McCann supporters

also lends weight to Grant’s views of ‘‘technological

populism’’ and ‘‘penal escalation’’ (Grant, 2007, p.

95).

This category also raised

issues of freedom of virtual speech, with vehement criticisms around

exclusion from ‘‘pro-McCann’’ dialogues. This debate took

issues of virtual community out into the general blogosphere, linking

to and commenting on external sites. To some extent, posters in this

genre appeared to view YouTube

as a necessary space for the expression of unpopular anti-McCann

sentiment subject to heavy moderation or silencing in other areas.

Given the common tendency throughout the comments analysed in both

genres to ban or mark as ‘‘spam’’ dissenting voices in their

midst, any sense of real free and open debate in the YouTube

community itself was actively undermined by the way users employed

the site’s own regulatory mechanisms.

Conclusion

YouTube offered a

space for a broad range of perspectives on this case and, in so

doing, accommodated viewpoints that in some cases challenged, and in

others drew heavily on mainstream mediations. Broadly speaking,

however, user-generated content and responses expanded the discursive

parameters of public response to the case. Elements of carnivalesque

and performative resistance jostled for a voice alongside the more

traditional articulations characterizing public displays of grief,

loss and vengeance in response to mediated child murder in

late-modern life.

Distinct virtual

communities clearly emerged, however, around specific perspectives

isolated in the generic categories. In responses to tribute videos,

the community was highly consensual around discourses articulating a

general anxiety around risk in late- modern society and, as such,

supported Greer’s (2004) observations around a desire to frame

these narratives in simplistic binary terms. Strenuous efforts to

disrupt this sense of imagined community were noted in the responses,

however, often employing humorous and graphic sexual content to

deliberately provoke conflict. In the hostility videos, community was

more dialogic and critical. Overall, both communities of response

proved as susceptible to the exclusion or marginalization of

dissenting voices as more mainstream mediations. However, the strong

thread of criticism around the British media’s handling of this

case, particularly in the hostility genre, indicates a shift in

consumer-producer relations facilitated by sites such as YouTube,

and supports the Polis Think Tank’s observation that many members

of the British public ‘‘don’t trust the media so they go to

Internet forums to express their views on the case’’ (Beckett,

2008).

Distinct features of the

case, such as the lack of narrative resolution, the McCanns’ own

unprecedented use of traditional and new media forms, and their

status as the professional parents of a photogenic child who

disappeared whilst unattended in a holiday apartment, need to be

considered when drawing conclusions about specific responses to this

case. Strong threads of debate around class, race, parenting, and

perceived ‘‘spin’’ from the McCanns were generated in

response to the specific

characteristics of the case. Similarly, the

lack of a known perpetrator allowed for a range of symbolic

representations of ‘‘other’’, and a generalized, diffuse

sense of risk at large. In the hostility videos at least, blame was

levelled firmly at Kate and Gerry McCann, contributing to a

schizophrenic approach to the McCanns as dual symbols of victimhood

and questionable parenting across the sample as a whole (Hume,

2007).

This paper has clearly

demonstrated that there is much potential for insight into the

complex relationships between the news narratives of child abduction

and audiences emerging through new technological interfaces such as

YouTube. The various

nuances, contestations and allegiances mapped within the broader

YouTube community in

response to this case resist simple dialectical categorizations of

either rational democratic debate or reductive populist binaries.

Rather, user-generated content and debate have been shown to extend

the terrain of corporate mediation and public response in a number of

ways that impact significantly on the production and consumption of

news narratives.

As members of the public

increasingly answer YouTube’s

rallying call to broadcast themselves, I return to Greer’s sense of

virtual communities as equally important conduits for ‘‘the

celebration of diversity and the articulation and advancement of

alternative discourses’’ (Greer, 2004, p. 108), as they are

repositories for particular communities of vicarious, affective

expression. As journalists and media scholars alike, we have much to

learn about evolving forms of public engagement with mediated crime

from the consensus, allegiances, and varied acts of resistance that

take place in sites such as YouTube.

YouTube a offert un espace pour un large éventail de perspectives sur cette affaire et, ce faisant, a accueilli des points de vue qui, dans certains cas, remettaient en question les médiations traditionnelles et, dans d'autres, s'en inspiraient fortement. De manière générale, cependant, le contenu et les réponses générés par les utilisateurs ont élargi les paramètres discursifs de la réponse publique à cette affaire. Des éléments de résistance carnavalesque et performative se sont bousculés pour se faire entendre aux côtés des articulations plus traditionnelles caractérisant les manifestations publiques de chagrin, de perte et de vengeance en réponse au meurtre d'enfant médiatisé dans la vie moderne.

Des communautés virtuelles distinctes ont toutefois clairement émergé autour de perspectives spécifiques isolées dans les catégories génériques. Dans les réponses aux vidéos d'hommage, la communauté était très consensuelle autour des discours articulant une anxiété générale autour du risque dans la société moderne tardive et, en tant que telle, elle a soutenu les observations de Greer (2004) sur le désir d'encadrer ces récits en termes binaires simplistes. Toutefois, les réponses font état d'efforts considérables pour perturber ce sentiment de communauté imaginaire, en recourant souvent à un contenu sexuel humoristique et graphique pour provoquer délibérément le conflit. Dans les vidéos sur l'hostilité, la communauté était plus dialogique et critique. Dans l'ensemble, les deux communautés de réponse se sont avérées aussi susceptibles d'exclure ou de marginaliser les voix dissidentes que les médiations plus traditionnelles. Cependant, le fort fil conducteur de la critique autour du traitement de cette affaire par les médias britanniques, en particulier dans le genre hostilité, indique un changement dans les relations consommateur-producteur facilité par des sites tels que YouTube, et soutient l'observation du Polis Think Tank selon laquelle de nombreux membres du public britannique " ne font pas confiance aux médias, alors ils vont sur les forums Internet pour exprimer leurs opinions sur l'affaire " (Beckett, 2008).

Les caractéristiques particulières de l'affaire, telles que l'absence de résolution narrative, l'utilisation sans précédent par les McCann des formes médiatiques traditionnelles et nouvelles, et leur statut de parents professionnels d'une enfant photogénique disparue sans surveillance dans un appartement de vacances, doivent être prises en compte pour tirer des conclusions sur les réactions spécifiques à cette affaire. Les caractéristiques spécifiques de l'affaire ont donné lieu à des débats animés sur la classe sociale, la race, l'éducation des enfants et la perception de l'influence des McCanns. De même, l'absence d'auteur connu a permis une série de représentations symboliques de "l'autre", ainsi qu'un sentiment généralisé et diffus de risque au sens large. Dans les vidéos sur l'hostilité au moins, le blâme a été porté fermement sur Kate et Gerry McCann, contribuant à une approche schizophrénique des McCann en tant que symboles doubles de la victimisation et de l'éducation douteuse dans l'ensemble de l'échantillon (Hume, 2007).

Cet article a clairement démontré qu'il existe un grand potentiel de compréhension des relations complexes entre les récits d'enlèvement d'enfants et les audiences émergeant des nouvelles interfaces technologiques telles que YouTube. Les diverses nuances, contestations et allégeances cartographiées au sein de la communauté élargie de YouTube en réponse à cette affaire résistent aux catégorisations dialectiques simples du débat démocratique rationnel ou des binaires populistes réducteurs. Au contraire, il a été démontré que le contenu et le débat générés par les utilisateurs étendent le terrain de la médiation des entreprises et de la réponse du public de plusieurs manières qui ont un impact significatif sur la production et la consommation des récits d'actualité.

Alors que les membres du public répondent de plus en plus à l'appel de YouTube à se diffuser eux-mêmes, je reviens à l'idée de Greer selon laquelle les communautés virtuelles sont des conduits tout aussi importants pour " la célébration de la diversité et l'articulation et la promotion de discours alternatifs " (Greer, 2004, p. 108), qu'elles ne le sont pour des communautés particulières d'expression affective par procuration. En tant que journalistes et spécialistes des médias, nous avons beaucoup à apprendre sur l'évolution des formes d'engagement du public envers la criminalité médiatisée à partir des consensus, des allégeances et des divers actes de résistance qui se produisent sur des sites tels que YouTube.

NOTES

- An ‘‘arguido’’, or ‘‘arguida’’ if female, normally translates as ‘‘formal suspect’’ in Portuguese law. It denotes someone whose status is more than that of witness, but who has not been arrested or charged. The status allows for a more accusatory line of questioning, but also affords legal protection such as the right to remain silent, and to legal representation (see Graham Keeley’s Q & A for Times Online for further information)

- The 3 Arguidos Forum

REFERENCES

BECK, ULRICH (1992 [1986]) Risk Society, Towards a New Modernity, Mark Ritter (Trans.), London: Sage.

BECK, ULRICH (1992 [1986]) Risk Society, Towards a New Modernity, Mark Ritter (Trans.), London: Sage.

BECKETT,

CHARLIE (2008) ‘‘McCanns and the Media: the debate’’,

Director’s Blog, Polis Journalism and Society.

BLACK,

TIM (2008) This Is More Than a Case of Media Maddieness

BURN,

GORDON (1995) Fullalove, London: Faber and Faber.

CASTELLS,

MANUEL (2001) Internet Galaxy: reflections on the Internet, business,

and society, Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

FEUER,

JANE (1992) ‘‘Genre Study and Television’’, in: Robert C.

Allen (Ed.), Channels of Discourse,

Resassembled (2nd edn), Chapel

Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, pp. 138-60.

GANNES, LIZ (2009) @Beet.TV: news video is a different beast

GIDDENS, ANTHONY (1991)

Modernity and Self-identity. Self and society in the late modern age,

Cambridge: Polity.

GRANT, CLAIRE (2007)

Crime and Punishment in Contemporary Culture, London: Routledge.

GREER, CHRIS (2004) ‘‘Crime, Media and Community: grief and virtual engagement in late modernity’’, in: Jeff Ferrell, Keith Hayward, Wayne Morrison and Mike Presdee (Eds), Cultural Criminology Unleashed, London: Glasshouse Press.

GREER, CHRIS (2004) ‘‘Crime, Media and Community: grief and virtual engagement in late modernity’’, in: Jeff Ferrell, Keith Hayward, Wayne Morrison and Mike Presdee (Eds), Cultural Criminology Unleashed, London: Glasshouse Press.

HARP, DUSTIN and

TREMAYNE, MARK (2007) Programmed by the People: theintersection ofpolitical communication and the YouTubegeneration, paper presented to the Annual Meeting of the

International Communication Association, San Francisco, 23 May

HUME, MICK (2007) TheIncreasingly Strange Case of Madeleine McCann, Spiked, 15

August

KITZINGER, JENNY (2004) Framing Abuse: media influence and public understandings of media violence against children, London: Pluto Press.

KITZINGER, JENNY (2004) Framing Abuse: media influence and public understandings of media violence against children, London: Pluto Press.

LARSEN, PETER (2002)

‘‘Mediated Fiction’’, in: Klaus Bruhn-Jensen (Ed.), A

Handbook of Media and Communication Research: qualitative and

quantitative methodologies, London: Routledge.

MALIK, KEENAN (2008) Mourning Sickness in a Culture of Fear

RHEINGOLD, HOWARD (1993) The Virtual Community:homesteading on the electronic frontier

SANTOS, RODRYGO L.T., ROCHA, BRUNO P.S., REZENDE, CRISTIANO G. and LOUREIRO, ANTONIO A.F. (2008) Characterizing the YouTubeVideo Sharing Community SUROWIECKI, JAMES (2004) The Wisdom of Crowds: why the many are smarter than the few and how collective wisdom shapes business, economies, societies and nations, New York: Doubleday.

RHEINGOLD, HOWARD (1993) The Virtual Community:homesteading on the electronic frontier

SANTOS, RODRYGO L.T., ROCHA, BRUNO P.S., REZENDE, CRISTIANO G. and LOUREIRO, ANTONIO A.F. (2008) Characterizing the YouTubeVideo Sharing Community SUROWIECKI, JAMES (2004) The Wisdom of Crowds: why the many are smarter than the few and how collective wisdom shapes business, economies, societies and nations, New York: Doubleday.

THE SUN (2009) ‘‘‘Maddie’

Perv Quiz’’, 10 June

THOMAS, DEEPAK and BUCH,

VINEET (2007) YouTubeCase Study: widget marketing comes of age,

Start Up Review:

Analyzing Web Success, 18 March

VAN DIJK, TEUN (Eds)

(1997) Discourse as Social Interaction, London: Sage.

YouTube

(2007a) Madeleine McCann get home safely video, 9 May

YouTube

(2007b) Madeleine McCann bring her home!!!!!!! video, 13

May

YouTube

(2007c) ‘‘Whooops, Looks Like Mommy and Daddy Did It!!!!!’’,

video, 10 September

YouTube (2007d) The Real Madeleine McCann Story Tapas video, 7 October

YouTube (2007d) The Real Madeleine McCann Story Tapas video, 7 October

YouTube

(2007e) My Madeleine McCann Opinion video, 2 November

YouTube

(2007f) Kate McCann on BBC Panorama video, 19 November

YouTube

(2008a) Madeleine McCann the McCann infantile memoryvideo, 14 January

YouTube

(2008b) Madeleine’s Coloboma Eye the McCann Strategy

video, 29 April

YouTube

EDITORS (2007) ‘‘Westward, Ho! YouTube’s

News & Politics Editor arrives’’